Prostate Cancer

About Prostate Cancer

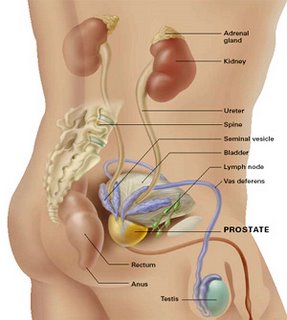

Prostate cancer is a form of cancer that develops in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system. The cancer cells may metastasize (spread) from the prostate to other parts of the body, particularly the bones and lymph nodes. Prostate cancer may cause pain, difficulty in urinating, problems during sexual intercourse, or erectile dysfunction. Other symptoms can potentially develop during later stages of the disease.

Causes

The specific causes of prostate cancer remain unknown. A man's risk of developing prostate cancer is related to his age, genetics, race, diet, lifestyle, medications, and other factors.

The primary risk factor is age. Prostate cancer is uncommon in men younger than 45, but becomes more common with advancing age. The average age at the time of diagnosis is 70. However, many men never know they have prostate cancer. Autopsy studies of Chinese, German, Israeli, Jamaican, Swedish, and Ugandan men who died of other causes have found prostate cancer in thirty percent of men in their 50s, and in eighty percent of men in their 70s. In the year 2005 in the United States, there were an estimated 230,000 new cases of prostate cancer and 30,000 deaths due to prostate cancer.

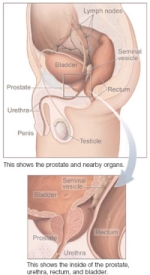

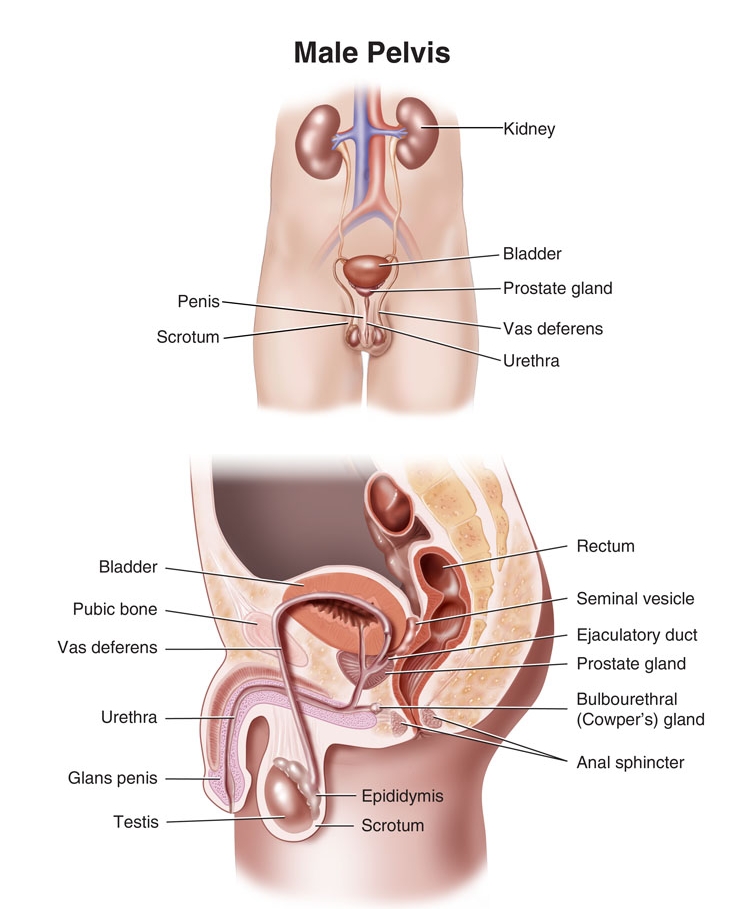

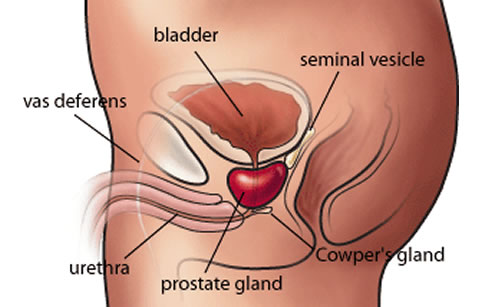

What is Prostate?

The prostate is a part of the male reproductive organ that helps make and store seminal fluid. In adult men, a typical prostate is about three centimetres long and weighs about twenty grams. It is located in the pelvis, under the urinary bladder and in front of the rectum. The prostate surrounds part of the urethra, the tube that carries urine from the bladder during urination and semen during ejaculation. Because of its location, prostate diseases often affect urination, ejaculation, and rarely defecation. The prostate contains many small glands which make about twenty percent of the fluid constituting semen. In prostate cancer, the cells of these prostate glands mutate into cancer cells. The prostate glands require male hormones, known as androgens, to work properly. Androgens include testosterone, which is made in the testes; dehydroepiandrosterone, made in the adrenal glands and dihydrotestosterone, which is converted from testosterone within the prostate itself. Androgens are also responsible for secondary sex characteristics such as facial hair and increased muscle mass.

Symptoms

A man with prostate cancer may not have any symptoms. For men who do have symptoms, the common symptoms include:

Urinary problems

- Not being able to pass urine

- Having a hard time starting or stopping the urine flow

- Needing to urinate often, especially at night

- Weak flow of urine

- Urine flow that starts and stops

- Pain or burning during urination

Difficulty having an erection

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Frequent pain in the lower back, hips, or upper thighs

Most often, these symptoms are not due to cancer. BPH, an infection, or another health problem may cause them. If you have any of these symptoms, you should tell your doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated.

Predisposing Factors

Age

The main risk factor for prostate cancer is age. Prostate cancer is rarely diagnosed before the age of 40. After 40, the incidence rises rapidly. PSA testing is not generally carried out on men aged under 50 unless they have significant risk factors. The rates of prostate cancer at different ages are as follows:

|

Age |

Percentage of men |

|

20–30 |

2–8% |

|

31–40 |

9–31% |

|

41–50 |

3–43% |

|

51–60 |

5–46% |

|

61–70 |

14–70% |

|

71-80 |

31–83% |

|

81–90 |

40–73% |

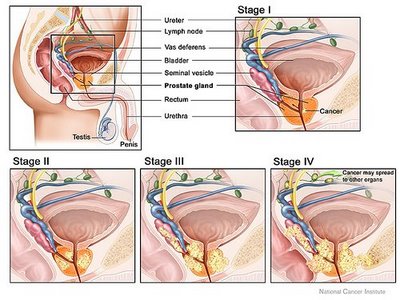

Stages

When prostate cancer spreads, it's often found in nearby lymph nodes. If cancer has reached these nodes, it also may have spread to other lymph nodes, the bones, or other organs.

When cancer spreads from its original place to another part of the body, the new tumour has the same kind of abnormal cells and the same name as the primary tumour. For example, if prostate cancer spreads to bones, the cancer cells in the bones are actually prostate cancer cells. The disease is metastatic prostate cancer, not bone cancer. For that reason, it's treated as prostate cancer, not bone cancer. Doctors call the new tumour "distant" or metastatic disease.

These are the stages of prostate cancer:

Stage I: The cancer can't be felt during a digital rectal exam, and it can't be seen on a sonogram. It's found by chance when surgery is done for another reason, usually for BPH. The cancer is only in the prostate. The grade is G1, or the Gleason score is no higher than 4.

Stage II: The tumour is more advanced or a higher grade than Stage I, but the tumour doesn't extend beyond the prostate. It may be felt during a digital rectal exam, or it may be seen on a sonogram.

Stage III: The tumour extends beyond the prostate. The tumour may have invaded the seminal vesicles, but cancer cells haven't spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage IV: The tumour may have invaded the bladder, rectum, or nearby structures (beyond the seminal vesicles). It may have spread to the lymph nodes, bones, or to other parts of the body.

Treatments

There are different types of treatment for patients with prostate cancer.

Different types of treatment are available for patients with prostate cancer.  Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Four types of standard treatment are used:

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting is closely monitoring a patient’s condition without giving any treatment until symptoms appear or change. This is usually used in older men with other medical problems and early- stage disease.

Surgery

Patients in good health are usually offered surgery as treatment for prostate cancer. The following types of surgery are used:

Pelvic lymphadenectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the lymph nodes in the pelvis. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells. If the lymph nodes contain cancer, the doctor will not remove the prostate and may recommend other treatment.

Radical prostatectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the prostate, surrounding tissue, and seminal vesicles. There are 2 types of radical prostatectomy:

- Retro pubic prostatectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the prostate through an incision (cut) in the abdominal wall. Removal of nearby lymph nodes may be done at the same time.

- Perineal prostatectomy: A surgical procedure to remove the prostate through an incision (cut) made in the perineum (area between the scrotum and anus). Nearby lymph nodes may also be removed through a separate incision in the abdomen.

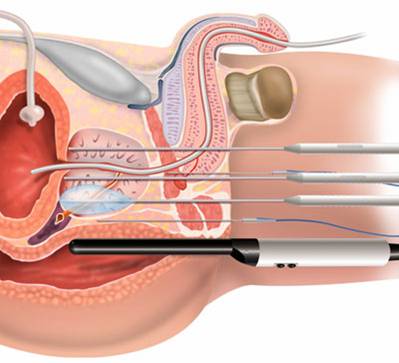

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP):

A surgical procedure to remove tissue from the prostate using a resectoscope (a thin, lighted tube with a cutting tool) inserted through the urethra. This procedure is sometimes done to relieve symptoms caused by a tumour before other cancer treatment is given. Transurethral resection of the prostate may also be done in men who cannot have a radical prostatectomy because of age or illness.

Impotence and leakage of urine from the bladder or stool from the rectum may occur in men treated with surgery. In some cases, doctors can use a technique known as nerve-sparing surgery. This type of surgery may save the nerves that control erection. However, men with large tumours or tumours that are very close to the nerves may not be able to have this surgery.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are two types of radiation therapy. External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer. Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer. The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

Impotence and urinary problems may occur in men treated with radiation therapy.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy is a cancer treatment that removes hormones or blocks their action and stops cancer cells from growing. Hormones are substances produced by glands in the body and circulated in the bloodstream. In prostate cancer, male sex hormones can cause prostate cancer to grow. Drugs, surgery, or other hormones are used to reduce the production of male hormones or block them from working.

Hormone therapy used in the treatment of prostate cancer may include the following:

- Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists can prevent the testicles from producing testosterone. Examples are leuprolide, goserelin, and buserelin.

- Antiandrogens can block the action of androgens (hormones that promote male sex characteristics). Two examples are flutamide and nilutamide.

- Drugs that can prevent the adrenal glands from making androgens include ketoconazole and aminoglutethimide.

- Orchiectomy is a surgical procedure to remove one or both testicles, the main source of male hormones, to decrease hormone production.

- Estrogens (hormones that promote female sex characteristics) can prevent the testicles from producing testosterone. However, estrogens are seldom used today in the treatment of prostate cancer because of the risk of serious side effects.

Hot flashes, impaired sexual function, loss of desire for sex, and weakened bones may occur in men treated with hormone therapy.

New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery is a treatment that uses an instrument to freeze and destroy prostate cancer cells. This type of treatment is also called cryotherapy.

Impotence and leakage of urine from the bladder or stool from the rectum may occur in men treated with cryosurgery.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly into the spinal column, an organ, or a body cavity such as the abdomen, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas (regional chemotherapy). The way the chemotherapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

Biologic therapy

Biologic therapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defences against cancer. This type of cancer treatment is also called biotherapy or immunotherapy.

High-intensity focused ultrasound

High-intensity focused ultrasound is a treatment that uses ultrasound (high-energy sound waves) to destroy cancer cells. To treat prostate cancer, an endorectal probe is used to make the sound waves.

The review of this section illustrates the treatment that is being studied in clinical trials. It may not mention every new treatment being studied.

Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today's standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

Some clinical trials only include patients who have not yet received treatment. Other trials test treatments for patients whose cancer has not gotten better. There are also clinical trials that test new ways to stop cancer from recurring (coming back) or reduce the side effects of cancer treatment.

Follow-up tests may be needed.

Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer or to find out the stage of the cancer may be repeated. Some tests will be repeated in order to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests. This is sometimes called re-staging.